Introduction

Preparing for a secure retirement just isn’t as easy it was 30 years ago. Investment returns were much more consistent on a year-to-year basis than they are today. There was no deluge of complicated investment options to choose from. You could either invest in major public companies like AT&T and General Electric, or you could buy one of a handful of mutual funds that were available at the time. Social Security was in the black and you didn’t have to worry about whether or not you would actually receive the benefits promised to you. You could work for a big employer and know that if you put in the work, you would have a secure job until the day you retired.

In the 80s and 90s, you could simply invest in an S&P 500 index fund and receive consistently good rates of return on your money. Between 1980 and 1999, there were only two years where the S&P 500 had a negative total annual return and they were both pullbacks of less than 5%. You could build up a nest egg inside of an IRA or a 401K plan and know that it would consistently grow by about 10% each year. You could withdraw 4% to 5% of your portfolio each year in retirement without eroding your portfolio value and even give yourself a raise every year in retirement to account for inflation.

Unfortunately, those days are gone. Between the crash of technology stocks in 2000, the 9/11 attacks in 2001 and the ongoing war on terrorism, the S&P 500 had three consecutive years of negative returns between 2000 and 2002. We had a couple of good years in the 2000s, but those returns evaporated when the S&P 500 lost 37% of its value in 2008 during the Great Recession. Major American corporations, like General Motors and Merrill Lynch, went bankrupt. Tax revenue fell sharply and the national debt doubled in just a few years. Interest rates fell to near zero and the government had to step in and provide an unprecedented economic stimulus to get the economy back on its feet.

We have had some good years since the Great Recession ended, but the promise of working for an employer for life and setting aside money in a 401K plan, then having a secure retirement has all but disappeared. Corporations are no longer loyal to their employees. Social Security is effectively insolvent. Financial experts are now telling us that we are going to have to work longer and live on just 3% of our investment portfolio during retirement.

We can no longer rely on the government or big corporations to take care of us during our retirement years. We can’t simply throw money at the S&P and expect to receive consistently good returns over the long term. These strategies may have worked for people retiring 25 years ago, but people who are in their 20s, 30s, 40s and 50s need a new investing game plan that will offer them superior returns, consistent growth, and the opportunity for a secure retirement.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Enter Dividend Investing

What if I told you that there was an investment strategy that could provide you with a secure stream of lifetime cash flow? If there was an investment strategy that would allow you to live off of 4% to 6% of your portfolio each year without having to ever sell shares of stock or touch your principal, would you be interested? What if this strategy was less volatile than the S&P 500 and has historically offered higher returns than the S&P 500? What if the income stream generated by this portfolio actually grew by 5–10% each year? Would you be interested?

This investment strategy actually exists and it’s not a super-secret hedge fund that’s only available to the ultra-wealthy, a little-known strategy that will stop working as soon as everyone knows about it, or the next Ponzi scheme waiting to unravel. This strategy is quite simple and frankly, incredibly boring—but it actually works. This miracle investment strategy is investing in dividend stocks. While it might not seem like there’s anything all that special about companies that pay dividends, the performance numbers will change your mind.

Standard and Poor’s keeps track of a list of S&P 500 companies that have grown their dividend every year for at least 25 consecutive years, known as the S&P Dividend Aristocrats Index. This group of 52 companies includes household names like 3M, AT&T, Chevron, Coca-Cola, Exxon Mobil, McDonald’s, Procter & Gamble and Wal-Mart. It would be natural to think that these long-established companies wouldn’t grow as fast as the broader market, but actual investment returns tell a different story.

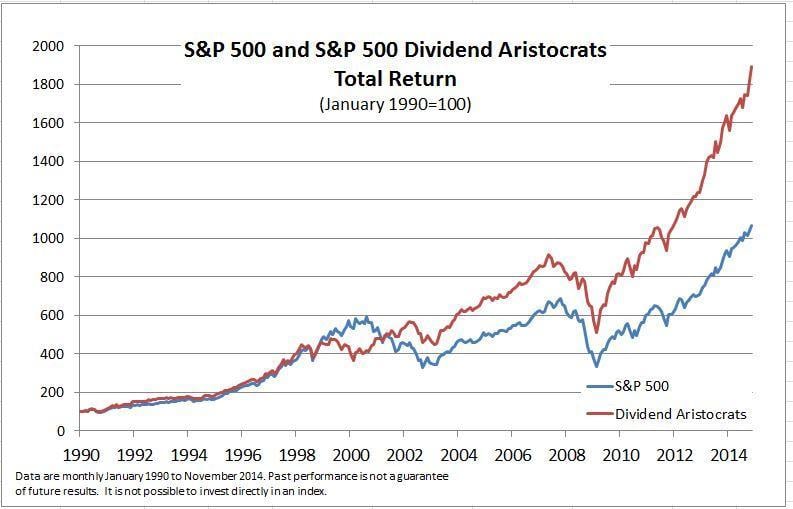

The Indexology blog recently published a chart comparing the performance of the S&P Dividend Aristocrats Index to the performance of the S&P 500 between 1990 and 2015. While investing in the S&P 500 resulted in cumulative returns of about 1,100% during this time frame, the S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats Index had cumulative returns of more than 1,900%.

During the ten-year period ending in September 2016, the S&P Dividend Aristocrats has indexed an average annual rate of return of 10.14% while the S&P 500 Index has returned an average annualized rate of return of just 7.22%. No one will deny that dividend stocks have had a good run during the last few decades, but what about over the long term? It turns out that dividend payments are responsible for 40% of the annualized returns of the S&P 500 over the last 80 years.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Do I have your attention now?

Dividend investing really works and you can make it work for you, too. You can use the power of dividend investing in your personal 401K plan, your IRA, and your individual brokerage account to create an investment portfolio of dividend growth stocks that will generate a steady income stream, be less volatile than the broader market, and offer returns that are superior to the S&P 500. You can build a dividend-stock portfolio that has an annualized yield of 4%–6% and that yield will grow by 5%–10% each year as companies raise their dividend over time. Dividend investing offers a perfect combination of income investing and growth investing. You get income from the dividend payments you receive as well as long-term capital gains from price appreciation in the stocks you invest in. If dividend stocks continue to perform as they have over the last 10 years, it’s not unreasonable to expect an annualized rate of return of 10% in the years to come.

Just about everyone who is investing their money has the same goal— to have enough money in savings and investments that you never have to work again (if you don’t want to). You might want to retire at age 65 or you might want to retire early at age 55. Maybe you never want to retire, but you want the freedom and flexibility to work part-time or take a job you are passionate about that doesn’t pay very well. Regardless of what your specific retirement goals are, dividend investing can help you achieve them. If you invest in dividend-growth stocks throughout your working lifetime, you can simply stop reinvesting your dividend payments at retirement and start living off the dividend payments you receive. You may never even have to sell any of the shares of stock you own, which will allow you to leave a significant inheritance for your children and your grandchildren.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

How to Earn $100,000 (Or More) Per Year in Retirement

Let’s imagine for a moment that you are 35 years old, are married, and have never saved a dime for retirement. You know that saving for retirement is important, but other things have just been a higher priority. You bought a house, you had a couple of kids, and you just never got around to opening a retirement account. You and your spouse decide it is time to take action and begin planning for your future and saving for retirement.

You and your spouse max out your Roth IRAs and invest $12,000 per year in dividend-growth stocks from age 35 through age 65. You don’t have a 401K plan through work, you don’t do any other investing, and you never increase the amount you’re saving each year. You earn an average rate of return of 10% per year and reinvest your dividends along the way. At age 65, you would have a total $2.26 million in your retirement account. If your portfolio were to have a dividend yield of 4.5%, you would receive $101,700 in dividend payments each year.

By simply maxing out your Roth IRAs and investing in dividend stocks for part of your working lifetime, you can have a retirement portfolio that will generate $100,000 per year in dividends. You won’t have to sell a single share of stock during retirement to pay for your lifestyle. You won’t have to take a part-time job as a greeter at Wal-Mart, and you won’t have to rely on the government paying you the Social Security payments you’ve been promised. Unlike most Americans, who retire broke, you’ll have a steady stream of cash deposits coming into your brokerage account each month from great American companies like Johnson & Johnson, Coca-Cola, General Electric, Verizon, Wal-Mart, and Wells Fargo.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

I love dividend investing.

In my role as the founder of MarketBeat, a financial-news service that makes real-time financial information available to investors at all levels, I have been looking for an investment strategy for the last six years that I could wholeheartedly recommend to the 425,000 people who subscribe to our daily newsletter. I evaluated the performance of just about every tried-and-true investment strategy and every hot new asset allocation. Almost without exception, every portfolio I looked at offered unremarkable returns, would only work well in certain market conditions, or simply couldn’t stand the test of time.

The only investment strategy I have found that has historically offered superior returns and has stood the test of time is dividend growth investing, which is the strategy I use in my own personal investment portfolio. At the time of this writing, my portfolio contains 30 dividend-growth stocks and a few other income-generating investments. My brokerage account currently has a dividend yield of 4.45% and the companies I invest in have raised their dividends by an average of 7.3% over the last several years. If my portfolio companies continue to raise their dividends at their current rate, I’ll be receiving a 9% dividend yield on my original investment after 10 years and an 18.2% dividend yield on my original investment after 20 years. My portfolio also happens to be 30% less volatile than the S&P 500 (as measured by beta) and has outperformed the S&P 500 since I started tracking my personal performance about three years ago.

I know what you’re thinking: “Just tell me what companies you bought!” The purpose of this guide is not to recommend any specific dividend stocks or suggest the companies that I currently own are superior to the broader market or will offer above-average returns in the years to come. Don’t just blindly copy someone else’s portfolio. The way to do well with dividend investing is to do your own research, understand the characteristics of high-quality dividend stocks, and build a portfolio of solid dividend-growth companies.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

What You’ll Learn

This guide is designed to be a primer for anyone looking to learn about dividend investing. It assumes you have a basic understanding of what stocks are and how the stock market works, but is very accessible to anyone who’s just getting started. Here’s what you’ll learn in this guide:

- The Case for Dividend Investing (Chapter 1) – You’ll learn why investing in dividend stocks is arguably the best way to invest in the stock market. You’ll learn how investing in dividend stocks compares to investing in broad-market indexes. You’ll learn about how risky dividend stocks are relative to other investments.

- Dividend Investing Basics (Chapter 2) – You’ll learn all of the terminology relevant to dividend investors. You’ll learn how announcement dates, ex-dividend dates, record dates, and payable dates work. You’ll learn about common types of dividend stocks, such as blue chips, real estate investment trusts, utilities, master limited partnerships, royalty trusts, and business development companies.

- Evaluating Dividend Stocks (Chapter 3) – You’ll learn to tell high-quality dividend stocks from the rest of the pack. You’ll learn why you shouldn’t always invest in the highest-yielding companies. You’ll learn how to evaluate the stability of a company’s dividend and its possibilities for long-term growth. We’ll also go through and analyze several stocks so that you can put your newly found research skills into practice.

- How to Discover Great Dividend Stocks (Chapter 4) – You’ll learn what websites, newsletters, and research tools I use personally to identify, research, and evaluate dividend stocks. You’ll learn more about the S&P Dividend Aristocrats Index and other lists of stocks with long track records of dividend growth. You’ll also learn several shortcuts to identify companies that pay great dividends and have strong long-term growth potential.

- Tax Implications of Dividend Investing (Chapter 5) – Not all dividend payments receive equal tax treatment. You’ll learn which types of companies’ dividends will be taxed at capital-gains rates and which will be taxed at your ordinary income rates. You’ll also learn how to invest in dividend stocks inside of a retirement account.

- How to Build a Dividend Stock Portfolio (Chapter 6) – We’ll put everything together in this chapter and show you how to build your very own investment portfolio of dividend stocks. You’ll learn whether you should invest in a dividend growth mutual fund or ETF or whether you should buy individual dividend stocks. You’ll learn if you should reinvest your dividends or if you should ever sell any of your dividend stocks. You’ll also learn how to actually start living off your dividend stock portfolio in retirement.

Of course, I don’t expect that this will be the only guide on dividends that you ever read. In Appendix One, I’ve included a number of books, newsletters, and websites that you can read to learn more about dividend investing. In Appendix Two, I’ve included a list of the companies on the S&P Dividend Aristocrats Index so that you have a starting point for your research. Appendix Three contains a legal disclaimer.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Let’s Get Started

The best time to start building your portfolio of dividend-growth companies was five years ago, but the second best time is today. It’s never too early or too late to start investing.

Every month that you let go by without saving for retirement is a month of missed dividend payments and missed capital appreciation.

Make a decision today that you are going to take control of your future and begin building your investment portfolio of dividend-growth stocks.

Take the first step toward planning a more secure retirement by reading the remainder of this guide and learning how to evaluate and invest in dividend stocks.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Chapter One: The Case for Dividend Investing

Before diving into the fine details of dividend investing, it’s worth taking a step back and thinking about what goals you are actually trying to accomplish through investing and how you might best achieve those goals. If you’re like most people, you’re dependent on the month-to-month income provided by your day job or your business. If you were to lose your job or if your business were to fail, you would be in a world of hurt after a few months. The goal is to set aside money for the future inside of IRAs and 401K plans so that you don’t have to continue to earn a paycheck in retirement. If you build a big-enough nest egg, you can live entirely off the money generated by investments and won’t have to work a part-time job to supplement your income in retirement.

The concept of putting money away to live on during retirement is pretty basic, but most people are miserable failures when it comes to saving retirement. Thirty-three percent of Americans have literally nothing saved for retirement, according to a study from GoBankingRates. Sixty-six percent of all Americans have less than $50,000 set aside for retirement, which will cover 1–2 years of retirement at most. Only 13% of Americans have set aside $300,000 or more for retirement. If you are part of the vast majority of Americans that aren’t saving enough for retirement, get ready to work a part-time job and eat beans and rice in retirement. Instead of playing with your grandchildren, taking life easily, and traveling around the world, you’ll be stuck stocking shelves in a grocery store or greeting people as they come into Wal-Mart. If that’s you, I implore you to start investing today so that you can have a better future.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Dividend Stocks Work Great for Retirement Investing

After you open up an IRA or set up a 401K plan through your employer, you have to decide what kind of investments you want to put your money into. If you’re younger, the standard advice is to put money away into growth stocks that have a good chance to appreciate over time as you get closer to retirement. You will probably do okay owning growth stocks throughout your working years, but they are non-ideal investments if you’re in retirement because you have to sell shares of the stocks or mutual funds you own to provide for your lifestyle. This might work okay when the market is doing well, but selling shares in a declining market will magnify the impacts of market losses. If the market declines by 2% in a year, you have to sell shares that were worth $62,500 a year ago just to get $50,000 in cash. This effect, known as reverse dollar-cost averaging, means the market will need a significantly stronger recovery to get you back to your original account balance. For example, if the market were to decline by 20% per year and you withdraw 4% of your money in a year, you will actually need a 31.6% recovery to get back to your original portfolio balance.

For people getting ready to retire, the standard advice is to purchase lower-risk, income-generating investments such as municipal bonds, corporate bonds, and treasury bills. These investments provide stability and the type of steady income stream that retirees are looking for, but they just aren’t able to generate the yields retirees need in the current protracted low-interest rate environment. As I write this chapter, a 10-year Treasury bill pays a yield of just 1.7%. The iShares National Municipal Bond Fund, the largest municipal bond fund, currently pays a dividend yield of just 2.26%. Since most retirees are looking to be able to safely live on at least 4% of their retirement portfolio each year, traditional income investments just aren’t going to cut it until the prevailing interest rates rise to more historical levels.

Dividend stocks offer the perfect mix of growth investing and income investing. You can build a portfolio of dividend stocks that offers immediate income in the form of dividend payments and long-term capital appreciation as the prices of your stocks rise over time. You can easily build a portfolio of dividend stocks that offer a yield by 4% and 5% in today’s environment, which will enable you to meet the target 4% withdrawal rate in retirement. You will also never have to sell any shares of the stocks that you own, because 100% of your withdrawals will be funded by the dividend payments that you receive. Since you’re never actually selling any of your shares, you won’t get hammered by the effects of reverse dollar-cost averaging in the event of a market dip.

Dividend stocks offer true passive income. You receive checks in the mail (or deposits in your brokerage account) every month or every quarter for simply owning a publicly traded company. You don’t have to do anything other than continue to hold on to your stocks. Because companies regularly raise their dividends, the passive income you receive in the form of dividend payments will almost certainly grow over time. There is also no guessing about how much money you can or cannot safely take out of your account, because you can immediately know how much income you can live off of by adding up the amount of dividend payments you expect to receive over the course of the year. Dividend investing isn’t without risk, but the combination of capital appreciation and income they offer make them very attractive investments for retirement.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Dividend Stocks Have Lower Volatility

Investors use a metric known as beta to determine the volatility, or systematic risk, of any given company relative to the market as a whole. Beta identifies the tendency of a company’s returns and price swings to track with the broader market. The S&P 500 has a beta of 1.0. Companies that move with the market will also have a beta of 1.0. Companies that have a beta of less than one are theoretically less volatile than the broader market. Securities that have a beta of greater than one are more volatile than the market as a whole. Most technology stocks have a beta higher than one because they are higher-risk and higher-growth investments. On the other hand, companies in more stable sectors, such as utilities and consumer staples, will generally have betas of less than one. For example, iShares U.S. Utilities ETF has a beta of just 0.08. That means for every $1.00 price swing in the S&P 500, the iShares U.S. Utilities ETF will move about 8 cents.

As you might expect, dividend stocks are collectively less volatile and have less systematic risk than the broader market. Most companies that pay dividends and continue to grow them over time are well established large-cap companies that have long histories of earnings growth. They have more predictable earnings and tend to weather uncertain times better. During market dips, dividend stocks generally don’t fall nearly as much as younger, high-growth companies do. For example, the ProShares S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats ETF (NOBL), which tracks the S&P Dividend Aristocrats Index, has a beta of 0.77. If you were to own all of the companies in the S&P Dividend Aristocrats, your portfolio would be 23% less volatile than the S&P 500.

Having a portfolio with lower volatility won’t give you better returns, but it will help you sleep better at night. Many investors make the mistake of selling when the market is in decline to avoid further losses and only get back into the market after it’s already significantly appreciated in value. By owning stocks that don’t jump around as much, you’ll have much less of a temptation to sell out your positions when there’s a market decline.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

The Psychological Advantage of Dividend Investing

Dividend stocks have another psychological advantage as well. In lieu of worrying about the day-to-day value of your portfolio, focus on the perpetually growing income stream you receive in the form of dividend payments. By changing the metric that you focus on from something that is very volatile to something that will generally move up and to the right, you will be much less tempted to sell your shares during a market decline. You really should be focusing on the amount of income generated by your portfolio anyway, because the amount of income your portfolio generates is really the metric that will matter in retirement.

In Warren Buffet’s 2013 annual letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders, Buffet told a story about a 400-acre farm he purchased for his son in 1986. I won’t repeat the story in its entirety, but Buffet used the example of his farm to provide a world-class commentary about why investors shouldn’t focus on the wildly fluctuating valuations of stocks:

If a moody fellow with a farm bordering my property yelled out a price every day to me at which he would either buy my farm or sell me his—and those prices varied widely over short periods of time depending on his mental state—how in the world could I be other than benefited by his erratic behavior? If his daily shout-out was ridiculously low, and I had some spare cash, I would buy his farm. If the number he yelled was absurdly high, I could either sell to him or just go on farming.

Owners of stocks, however, too often let the capricious and often irrational behavior of their fellow owners cause them to behave irrationally as well. Because there is so much chatter about markets, the economy, interest rates, price behavior of stocks, etc., some investors believe it is important to listen to pundits—and, worse yet, important to consider acting upon their comments.

Those people who can sit quietly for decades when they own a farm or apartment house too often become frenetic when they are exposed to a stream of stock quotations and accompanying commentators delivering an implied message of “Don’t just sit there, do something.” For these investors, liquidity is transformed from the unqualified benefit it should be to a curse.

A “flash crash” or some other extreme market fluctuation can’t hurt an investor any more than an erratic and mouthy neighbor can hurt my farm investment. Indeed, tumbling markets can be helpful to the true investor if he has cash available when prices get far out of line with values. A climate of fear is your friend when investing; a euphoric world is your enemy.

During the extraordinary financial panic that occurred late in 2008, I never gave a thought to selling my farm or New York real estate, even though a severe recession was clearly brewing. And, if I had owned 100% of a solid business with good long-term prospects, it would have been foolish for me to even consider dumping it. So why would I have sold my stocks that were small participations in wonderful businesses? True, any one of them might eventually disappoint, but as a group they were certain to do well. Could anyone really believe the earth was going to swallow up the incredible productive assets and unlimited human ingenuity existing in America?

(source: Berkshire Hathaway)

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

J.P. Morgan Asset Management issued a report in 2013 that analyzed how companies that pay dividends performed compared to companies that don’t pay dividends over a 40-year period. From January 31, 1972, to December 31, 2012, companies that paid no dividends had average annual returns of just 1.6%. Companies that cut or eliminated their dividends had average annual returns of -0.3%. On the other hand, companies that initiated or grew their dividends during that 40-year window saw average annual returns of 9.5% (source: ny529advisor.com).

It shouldn’t be much of a surprise that companies that pay and grow their dividends have outperformed that companies that don’t, since 40% of returns of the S&P 500 over the last 80 years have come from dividend payments. Let’s imagine that you invested $10,000 into an S&P 500 Index fund at its inception in 1926. If you had reinvested all of the dividend payments you received, your portfolio value would have grown by an average of 10.4% per year and would be worth $33,100,000 by the end of 2007. If you had not reinvested your dividends, your portfolio would have grown just 6.1% per year and would only be worth $1,200,000 at the end of 2007. During the 81-year period between 1926 and 2007, reinvested dividend income accounted for nearly 95% of the compound long-term return earned by companies in the S&P 500 (source: etf.com).

If you need further proof that companies that pay strong dividends regularly outperform the market, you need not look further than the S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats Index. This group of 52 S&P 500 companies that have raised their dividend every year for at least 25 years has dramatically outperformed other market indexes over the last decade. During the 10-year period ending in September 2016, the S&P 500 Index had an average annualized return of 11.68% with dividends reinvested. During the same period, Dividend Aristocrats Index returned an average annualized return of 16.17%. It’s hard to understate how dramatically dividend-paying stocks have outperformed the broader market given that they have outperformed the S&P 500 by a whopping 4.5% every year.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

You can’t fake dividend payments.

When publicly traded companies announce their earnings each quarter, the numbers presented are often largely a product of accounting and may not be truly representative of the company’s actual financial health. Skilled accountants and unscrupulous executives can make a bad company’s financials look healthy on paper. This is exactly what happened with Enron in the late 1990s. On paper, the company’s financials looked great. Behind the scenes, the company was transferring its losses and debts to offshore corporations that weren’t included in its financial statements. The company engaged in numerous sophisticated accounting transactions between various legal entities to eliminate unprofitable entities from its financials. Everything looked acceptable on paper, the company’s stock price remained strong, and it had a sterling credit rating, but it was a house of cards behind the scenes and eventually collapsed.

Accounting numbers can be manipulated, but you can’t fake dividend payments. Either a dividend payment appears in a company’s shareholders’ brokerage accounts, or it doesn’t. There are no accounting tricks that can make a dividend payment look stronger than it actually is and you know that the company at least has enough money to make its dividend payments. This isn’t to say that dividend payments necessarily mean that a company has strong cash flow, because companies will occasionally borrow money to pay their dividend during cyclical downturns. For example, Chevron has been borrowing to maintain its dividend recently because of cyclically lower oil prices. However, major financial institutions would never lend Chevron the money to cover its dividend payments if they didn’t believe that it would be able to repay those obligations in the years to come.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Dividend Payers Tend to Be Healthy Companies

Companies that pay strong dividends and steadily raise them over time tend to be very healthy and shareholder-friendly. One of the best signs of a company’s overall health is having strong positive cash flow (having new money come into the company) and a company cannot pay dividends over a long period of time unless they have the cash flow to support their dividend. Strong dividend payers also can’t carelessly acquire companies or launch speculative growth projects nearly as easily other companies that have similar cash flow but don’t pay dividends. They have to cherry-pick the growth opportunities that are most likely to create shareholder value with their artificially constrained retained earnings. Any company that can return more and more profit to its shareholders each year for decades must be doing something right.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Dividend Stocks Protect Against Inflation

Dividend-growth stocks offer a much better hedge against inflation than bonds and other fixed-income investments. Most bonds pay a fixed interest rate over the life of the bond, meaning the interest payment you receive is the same in the first month you own the bond as it is through its maturity (which could be more than a decade down the line). During inflationary periods, each successive interest payment that you receive has less purchasing power than the last. Because the bonds you own will be lower than the prevailing interest rate, the value of your bonds will decline to match the bond market’s current rates.

Dividend stocks won’t be immune to the effects of inflation, but publicly traded companies can at least raise their prices to match inflation, which will then be reflected in its annual earnings and dividend payments. According to data collected by Robert Shiller, dividends from the S&P 500 have grown at an annual rate of 4.12% between 1912 and 2005, while the Consumer Price Index (a commonly accepted measure of inflation) has risen by 3.3% annually during the same period. As long as a company grows their dividend as fast as or faster than the rate of inflation, shareholders’ dividend payments won’t lose any purchasing power.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Risks of Investing in Dividend Stocks

There’s a lot to like about dividend investing, but dividend stocks aren’t without risk either. There are several investment risks associated with dividend stocks that you should be aware of and factor into your investment decisions:

- Tax Policy Risk – Currently dividends receive preferential tax treatment under the U.S. tax code. Qualified dividend payments are taxed at capital-gains rates, which are either 15% or 20% depending on your tax rate. It hasn’t always been this way, though. As you’ll learn in a later chapter, Congress has toyed with dividend tax policy several times over the last decade. If Congress were to remove the preferential treatment that dividend payments receive, dividend stocks would be less attractive investments and would likely fall in price.

- Interest Rate Risk – Dividend yields are regularly compared to the interest rates offered by other fixed-income investments on a relative basis. When interest rates offered by risk-free dividend investments rise, dividend stocks become less attractive relative to their fixed-income counterparts. As interest rates rise, there will be natural outflows from dividend stocks that will lower their share price and drive up the yield of dividend stocks.

- Risk of Price Volatility – Dividend stocks have the same risks that any other publicly traded companies have. Their prices will fluctuate as market conditions change. While stocks generally perform well over the long term, investors must be prepared for years where their share prices decline significantly. If you can’t stomach a 30% decline in the price of your dividend stocks in a year, dividend stocks might not be the investment for you.

- Risk of Dividend Payment Cuts – When a company faces economic hardship, its ability to generate cash flow and thus make dividend payments will be constrained. If a company doesn’t have the cash flow to support its dividend over the long term, it will have to cut its dividend eventually. The share prices of companies that cut their dividends tend to take a significant beating in the market, so it’s important to monitor the companies in your portfolio for clouds on the horizon. If the company’s dividend appears unsustainable, you should try to get out before the company announces it will be cutting its dividend.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Summarizing the Case for Dividend Investing

There are a lot of qualitative reasons to like investing in dividend stocks, but what really matters at the end of the day when comparing investment options is risk-adjusted after-tax performance. In other words, how much of a financial return am I going to get for the level of risk I am taking on after all taxes are paid? In this chapter, I have shown you how dividend stocks have handily outperformed the S&P 500 and other asset classes over the last few decades. I have also demonstrated how dividend stocks are less volatile and have lower systematic risk than other publicly traded companies. Dividend payments also receive preferential tax treatment under current U.S. tax law. While dividend stocks aren’t without risk, the numbers demonstrate they are very attractive relative to other investments.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Chapter Two: Dividend Investing Basics

Let’s imagine for a moment that you have a friend named Michaela and that she is starting a new company that will offer customized IT solutions to other small business. Michaela needs some money to get her business off the ground. She approaches you and offers to sell you a 25% equity stake in the business in exchange for $50,000.00. You want to help out Michaela and think her business has merit and could generate significant profits, so you decide to take the deal and invest in her company. You are now a minority partner in an IT consulting business. You don’t take home any profit for the first year, but Michaela’s company starts to generate some meaningful profit during the second year. Michaela decides that she doesn’t need to keep all of the money in the business and declares a dividend at the end of the year. As a 25% owner in the business, you are entitled to receive 25% of the dividend that is paid out. Michaela mails you a check for your share of the company’s dividend at the end of the year and continues to do so as long as the company makes money and you remain a shareholder of her company. This is dividend investing in action.

It’s easy to think of stocks, dividends, and other financial concepts as abstract terms that have no relation to the real world, but owning shares of a publicly traded company isn’t that different than investing in a friend’s business. If you were to buy shares of Coca-Cola, you would become a minority owner of that company. Your ownership interest is equal to whatever percentage of the outstanding shares that you own. You and the other shareholders of Coca-Cola vote to elect a board of directors, which is responsible for overseeing the affairs of the business each year at the company’s annual meeting, either in person or online through proxy voting. When Coca-Cola makes a profit, the board that you helped elect can decide what to do with the money at the end of each quarter. They can hold on to it as retained earnings. They can reinvest it into the business or they can decide to return it to their shareholders in the form of a dividend payment. When Coca-Cola’s board of directors decides to distribute part of the company’s profit in the form of a dividend, you are entitled to your share of the profit distribution as a part-owner in the company. On the date set, your dividend payment will be routed to the brokerage account where you own the stock, at which point you can reinvest the dividend payment to get more shares or spend the money however you like.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

How Dividend Payouts Work

One might think that it would be easy to determine which shareholders are entitled to receive a dividend payment, but hundreds of millions of dollars in shares of every large-cap company are bought and sold every day and it’s not always intuitive regarding who should receive a dividend payment. For example, if you owned shares of Coca-Cola and I bought them from you after a dividend was declared, but before it was paid out to shareholders, which one of us should receive the dividend? Obviously, this isn’t the first time this question has been asked. There are a number of important dates to be aware of whenever a company announces a dividend:

- Declaration Date – The dividend declaration date is simply the date that a company’s board of directors publicly announces an upcoming dividend. This date has no impact on who receives a dividend payment.

- Ex-Dividend Date – The ex-dividend date is the day on which any new shares that are bought or sold are no longer eligible to receive the next scheduled dividend. If you want to receive a company’s next dividend payment, you must buy your shares prior to market close on the day before the ex-dividend date. Having an ex-dividend date a few weeks before a dividend is payable makes it easier for a company to reconcile which shareholders are eligible to receive a dividend payment.

- Record Date – Shareholders must properly record their ownership on or before the record date (or date of record) to receive a dividend payment. Shareholders who don’t register their ownership by this date will not receive a dividend payment. In the United States and most other countries, registration is automatic and not something you need to worry about.

- Payable Date – This is the date when dividend payments will actually be mailed to shareholders or credited to their brokerage account.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

A Note About “Dividend Capture” Strategies

Since the only date that matters when determining who receives a dividend payment is the person who owns it at the end of the ex-dividend date, one might think it would be easy to game the system by only buying shares of companies going ex-dividend the following day, holding them for 24 hours, then selling them to receive a dividend payment without actually having to hold on to the stock. You could then buy shares of new companies every day and capture as many dividend payments as there were trading days in a month. This “dividend capture” strategy sounds like a great idea in theory and there are people who have actually tried to teach it as an investment strategy, but it almost never works in practice.

When a company goes ex-dividend, its stock price will generally decrease by a dollar amount roughly equivalent to the amount of the dividend paid. Companies do not explicitly take any action to lower their share prices because buyers and sellers will automatically price in the lack of the upcoming dividend into the company’s stock price. These natural adjustments prevent people from trying to game the dividend system and capture dividend payments without owning a stock for more than one day at a time. Dividend capture strategies are very difficult to time correctly, rarely ever work, and are not something that I would recommend that you try to pursue.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Why Companies Pay Dividends

Companies that are growing rapidly generally don’t pay dividends, because they want to put most of their cash flow from earnings back into growing the company. Fast-growing companies may use earnings to start a new division, purchase new assets, buy out another company, or fund other growth projects. For this reason, many technology companies including Amazon and Alphabet (Google) don’t pay dividends. Additionally, companies that are more established may not pay dividends if they believe that they can create more shareholder value by reinvesting their earnings than by paying a dividend. This is the reason why Warren Buffet’s company, Bekrshire Hathaway, does not pay a dividend. On a side note, Berkshire Hathaway does invest in a variety of dividend-paying stocks, such as Coca-Cola, General Motors, IBM, and Wells Fargo.

Established companies with mature business models generally do not need to reinvest their earnings at the same rate that high-growth companies do. When a mature company finds itself with excess earnings, it may return a portion of those earnings to their shareholders in the form of a dividend. Many investors like the steady income that dividend-paying stocks offer and see dividend payments as a sign that the company is strong and that management believes the company will continue to have solid future cash flow. Mature companies will often pay dividends to attract new shareholders, to create greater demand for their stock, and to drive up the price of their stock.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Regular vs. Special Dividends

There are two general types of dividend payments. Regular payments are made on a set schedule, such as every month or every quarter. Most publicly traded companies will pay dividends every quarter, but some stocks, ETFs, and mutual funds will pay monthly. Some international companies only pay dividends once or twice per year. The amount of a regular dividend payment is generally pretty consistent from quarter to quarter, unless a company decides to raise or lower its dividend because of changes in earnings and cash flow. Almost all of the dividends that you receive will be regular dividend payments. Special dividends are one-time payments made to shareholders when a company finds itself with excess cash or disposes of an asset. For example, Microsoft issued a one-time special dividend of $3.00 per share in 2004 as a way to relieve its balance sheet of a large cash balance.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Types of Dividend Payments

Most dividend payments are provided to shareholders in the form of cash, but there are actually several different types of dividend payments. Here are some of the different types of dividend payments that you may run into as an investor:

- Cash Dividends – These are by far the most common type of dividend and will account for the vast majority of the dividend payments you receive. Cash dividends are simply a transfer of your share of a company’s earnings to your brokerage account in the form of cash.

- Stock Dividends – A stock dividend is the issuance of new shares of stock to existing shareholders without any consideration (payment) provided in exchange for the new shares. For example, if a company declared a 5% stock dividend and you owned 10,000 shares, you would receive 500 new shares of the company. While stock dividends increase the total number of outstanding shares of a company, they don’t increase the value of the company. A company that has a market cap of $1 billion isn’t suddenly worth $1.05 billion just because they issue a 5% stock dividend. Effectively, a stock dividend is a minor form of a stock split designed to increase the number of outstanding shares in the market.

- Property Dividends – Companies may issue non-monetary dividends to their shareholders. A property dividend could come in the form of shares of a subsidiary company or be physical assets such as inventories the company holds. For tax purposes, property dividends are recorded at the value of the assets provided to shareholders.

- Scrip Dividends – When a company does not have enough money to make its dividend payments, it may issue a scrip dividend, which is effectively a promissory note to pay shareholders a cash dividend at some date in the future.

- Liquidating Dividends – A liquidating dividend is a return of the capital that was originally contributed by shareholders. This type of dividend often occurs when a company is getting ready to shut down their business.

As a dividend stock investor, almost all of the dividend payments you will receive will be simple cash dividends. It is also possible that you will receive a stock dividend if a company wants to increase the number of shares it has in the marketplace without doing a full-on stock split. You may receive a property dividend if a company is spinning out a subsidiary as an independent company. Scrip dividends and liquidating dividends are very rare and you are unlikely to receive them as a dividend stock investor.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Types of Dividend Stocks

When we think of a dividend-paying stock, we generally think of established blue-chip companies such as Johnson & Johnson and General Electric. There are actually many different types of dividend-paying publicly traded companies that operate in different industries, have different corporate structures, have different tax liabilities, and have other characteristics that you should be aware of. The next several sections of this chapter outline some of the major categories of dividend-paying stocks that you might choose to invest in. The tax treatment for each of these types of stocks is discussed in a later chapter.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Consumer Staples

Companies that sell products that consumers use from day-to-day, such as beverages, household products, personal products, and tobacco are labeled as consumer staples. Proctor and Gamble (PG), Coca-Cola (KO), Philip Morris (PM), and Unilever (UN) are examples of consumer-staples companies. Consumer-staples companies sell products that are non-cyclical, meaning that consumers still generally need to buy their products during an economic downturn. As a result, these companies tend to have relatively consistent earnings and cash flow. These companies also tend to be very well established and have large market caps as a result of consolidation that has happened over the years, which makes them perfect candidates to pay dividends.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Banks

Many large banks were established dividend payers that offered yields between 3% and 5% before the Great Recession. When falling asset prices wreaked havoc on their balance sheets in 2008 and 2009, almost all of them had to dramatically cut their dividends. Since then, many of the large banks have slowly started raising their dividend payments again. Many are currently paying dividend yields between 1.5% and 3%. There are a few banks, most notably Wells Fargo, that are beginning to pay dividend yields that are consistently higher than the S&P 500. At this point, it’s hard to say whether or not banks as an asset class will return to their former glory of being high-dividend payers.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Energy Companies

Large-cap energy companies, like British Petroleum (BP), Chevron (CVX), and ExxonMobil (XOM), have a history of paying strong dividends. When energy prices are low, as they have been in the last year, these stocks’ share prices take a beating and their dividends rise. As I write this chapter, crude oil is hovering around $45.00 and major energy companies are paying dividend yields between 4% and 7%. When oil prices increase at some point in the future, oil producers’ stock prices will rise in tandem and their dividend yields will decrease to their more historic range of 3% to 5%.

Master limited partnerships (MLPs) are a subset of energy companies that are structured as publicly traded limited partnerships. Investors who buy units (shares) of MLPs become limited partners in the business and the company is run by its general partners (the company’s management). The MLP structure is used almost exclusively for energy and utility companies. MLPs have some unique tax advantages because of their corporate structure, which are explained in detail later on in this guide. MLPs tend to own energy pipelines and terminals, which makes them less sensitive to energy prices than large-cap energy production companies are. MLPs tend to have strong and consistent cash flow, which allows them to pay above-average dividends. It is not uncommon for MLPs to have dividend yields between 5% and 8%. Examples of MLPs include Spectra Energy Partners (SEP), Magellan Midstream Partners (MMP), and Enterprise Products Partners (EPD).

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Royalty Trusts

Royalty trusts, like master limited partnerships, invest in assets in the energy sector. Royalty trusts generate income from the production of natural resources like coal, oil, and natural gas. Royalty trusts have no actual employees or operations of their own. They are simply publicly traded financing vehicles that allow large energy production companies to lease natural resource assets. Royalty trusts are operated by banks, which manage their financial interests, take care of their paperwork, and make distributions to shareholders. Royalty trusts’ cash flow and distributions can swing wildly as commodity prices and production levels change, which causes them to have very inconsistent earnings from one year to the next.

The largest royalty trust in the United States is the San Juan Basin Royalty Trust (SJT), which owns oil and natural gas resources in the San Juan Basin of northwestern New Mexico. It is operated by Burlington Resources, a privately held oil-exploration-and-production company. Burlington Resources pays production royalties to SJT, which are then paid to shareholders of SJT in the form of distributions. SJT is managed by Compass Bank, a subsidiary of BBVA.

Many royalty trusts pay very high dividend yields, often in excess of 10%. Royalty trusts also have some unique tax benefits, which are described in detail in Chapter 5. While royalty trusts pay high yields, remember that the distribution payments they make are tied directly to the underlying price of the commodity owned by the trust. A wild swing in energy prices could dramatically change the value of your investment in a royalty trust as well as the dollar amount of distributions you receive. Commodity prices can be very volatile, so prepare for a wild ride if you choose to invest in a royalty trust.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Utilities

Utilities companies tend to be very stable and predictable businesses that generate strong cash flow. Because consumers will always need water, electricity, natural gas, propane, and home heating oil to provide for their basic needs, utilities companies tend to weather economic downturns particularly well. Utilities also operate as franchises that give them the exclusive right to supply electricity, water, or natural gas to a particular area, which means they don’t really have to worry about a competitive company coming in and eating their lunch. Utilities companies have huge infrastructure requirements and can use the same infrastructure for decades. It simply wouldn’t be cost effective for a new company to come in and try to rebuild existing infrastructure from scratch.

Utilities tend to be heavily regulated because of the monopoly positions they hold. State agencies establish standardized rates that utilities can charge for electric, water, and natural gas to prevent the abuse of monopoly power. These rates generally allow a utility to cover its normal operating expenses plus a fixed percentage of profits on top of those operating expenses. The profit margin that is permitted to utilities companies will vary from state, but target returns on equity of 10% to 12% are common. A utilities company’s profit will be determined primarily based on how much water, electricity, or natural gas they deliver to consumers. If the company is generating a higher profit margin than state regulators desire, the regulators can force a rate cut. Conversely, if costs come in much higher than expected, utilities businesses can ask state regulators for a rate hike to cover their increased costs.

From an investment perspective, utilities tend to have relatively stable share prices and have limited opportunity for long-term capital gains. Utilities also tend not to raise their dividend much faster than inflation and generally pay out 60% to 80% of their earnings in the form of a dividend. Although utilities offer limited long-term capital gains and dividend growth, they tend to offer very high dividend yields to attract investor dollars. Utilities companies currently pay dividend yields between 3% and 6%.

Examples of large utilities companies include Duke Energy Corp (DUK), National Grid Plc (NGG), Southern Co. (SO), American Electric Power (AEP), and Pacific Gas & Electric (PCG).

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Real Estate Investment Trusts

Real estate investment trusts (REITs) are a special type of corporate entity used to own and operate income-producing commercial real estate, such as restaurants, hotels, malls, warehouses, and hospitals and other medical facilities. REITs can either be publicly traded on a stock exchange or privately held. Publicly traded REITs give individual investors the opportunity to invest in commercial real-estate projects while maintaining the liquidity of their investment, meaning they can sell their shares on public markets at any time. REITs are required by law to pay out 90% of their earnings as dividends to their shareholders, which means they tend to offer above-average dividend yields. REITs also have different tax treatment than most other types of dividend stocks, which is addressed in detail in a later chapter.

Publicly traded REITs can either be set up as property REITs (sometimes called equity REITs), where the REIT owns interest in commercial real estate, or as mortgage REITs, where the REIT owns mortgages on commercial real-estate projects. Property REITs and Mortgage REITs have very different investment characteristics. Property REITs primarily make money by leasing space to commercial tenants and distribute the rent payments they receive as distributions to shareholders. Property REITs generate very predictable income and can make steady dividend payments because their commercial tenants are often locked into multi-year leases with set payment schedules.

Mortgage REITs borrow money commercially and lend it out to commercial real-estate projects in the form of mortgages. Mortgage REITs make their money on the spread between the interest rate at which they borrow money and the interest rate at which they lend money, which makes them very sensitive to changes in prevailing interest rates. Mortgage REITs tend to do well in declining-interest-rate environments where they lock in longer-term mortgages and can borrow money at increasingly affordable rates as prevailing interest rates lower. Conversely, they tend to do poorly when interest rates are rising and the spread between the rates at which they can borrow money and can loan money narrows.

Mortgage REITs tend to offer much higher interest rates than property REITs, but their share prices and dividend payments tend to be much more volatile than property REITs. Because of the volatility of mortgage REITs and the unpredictability of future dividend payments, many dividend investors avoid investing in mortgage REITs and focus exclusively on property REITs.

Examples of REITs include Public Storage (PSA), Welltower (HCN), Ventas (VTR), AvalonBay Companies (AVB), and Simon Property Group (SPG).

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Preferred Stocks

Preferred stock is a special classification of stock ownership that has a higher-priority claim on a company’s assets, earnings, and dividend payments than common stock. If a company falls upon hard times, its preferred stockholders must be paid their dividends before common stockholders receive any dividend payments. Preferred stockholders generally receive higher dividend yields than common stockholders, but the dividend payments on preferred stock are fixed and will not grow over time. Preferred stocks are said to have features of both stocks and bonds, because they offer fixed-income payments and also offer some opportunity for capital appreciation. Preferred shares generally do not come with voting rights in the company that issues them.

Some preferred shares are callable, meaning that the issuer can buy them back after a set date for a pre-determined share price. If interest rates decline, a company may buy back its existing preferred stock and reissue a new series of preferred stock with a lower dividend yield to save money. If interest rates are rising, a company will be less likely to buy back its preferred shares because it is effectively borrowing money at a below-market interest rate. Other preferred shares may be converted to common stock on a set date or by a vote of the company’s board, depending on the original terms specified for the preferred stock issue. Whether or not a conversion to common stock is profitable for preferred stock investors largely depends on the market price of the company’s common stock.

Many investors are attracted to preferred stock because of their above-average yields and stable share prices, although it can be a lot of work to research individual preferred stock issuances. In addition to evaluating the company’s prospects, investors must also research the characteristics of the individual preferred stock issue they are considering buying. For this reason, many preferred stock investors buy preferred stock mutual funds and ETFs and delegate the work of selecting individual preferred stock issuances to professional money managers. Preferred stock mutual funds and ETFs generally pay dividend yields between 5% and 8% in today’s market.

For example, the iShares US Preferred Stock Fund (PFF) is a popular ETF that primarily invests in preferred stock issuances offered by large financial institutions. It has a dividend yield that hovers between 5% and 6% and currently has a beta of just 0.29, which means its price is only about 30% as volatile as the broader market. It charges an expense ratio of 0.47%, which is in line with the fees charged by other preferred stock ETFs.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Business Development Companies

Business development companies (BDCs) are a special type of corporate entity that was created in the 1980s to encourage the investment of publicly traded funds into private equity investments. BDCs invest growth capital into small and medium-sized businesses in exchange for equity position, much in the way that private equity funds and venture capital (VC) funds do. However, VC funds are typically only accessible to accredited investors who meet very high net worth or income requirements. BDCs are usually publicly traded, which allows anyone to buy shares of them without meeting the accredited investor status requirement.

Business development companies have very specific legal requirements under the Investment Company Act that they must follow. According to Wikipedia, the Investment Company Act “(a) limits how much debt a BDC may incur, (b) prohibits most affiliated transactions, (c) requires a code of ethics and a comprehensive compliance program, and (d) requires regulation by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and subject to regular examination, like all mutual funds and closed-end funds. BDCs are also required to file quarterly reports, annual reports, and proxy statements with the SEC.”

Business development companies, just like real estate investment trusts, must distribute 90% of their income to shareholders, but most BDCs distribute as much as 98% of their earnings as distributions so that they can avoid taxation at the corporate level. Because of this profit-distribution requirement, BDCs tend to offer extremely high dividend yields that can range between 7% and 20%. Don’t be mistaken, though. There is no free lunch here. BDCs are effectively the rocket fuel of the dividend-investing world. They can offer dividend yields that you can’t find anywhere else, but they are also very volatile, have inconsistent dividend amounts and can blow up in your face if you’re not careful. BDCs invest in privately held micro-cap companies and can have very wild price swings that make the great dividend payments you receive moot.

Many dividend investors, including myself, avoid investing in BDCs altogether because of their wild volatility and inconsistent payout amounts. BDCs can be exciting to watch, but they simply don’t fit the mold most income investors are looking for—established players that have consistent and growing dividend payments over time.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Summary of Dividend Investing Basics

Some of the concepts and types of corporate structures in this chapter may be hard to remember at first. Fortunately for you, there’s no quiz at the end of this guide. Use this chapter as a reference guide to review dividend-investing concepts and how different corporate structures work when evaluating individual companies. Always be mindful of the types of corporate structures that companies that you invest in use, because each corporate structure has unique tax rules and investment characteristics.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Chapter Three: How to Select Dividend Stocks

As you begin to research dividend-paying stocks, you may be tempted to open your favorite stock screener, sort companies by their dividend, and focus on the companies that pay the highest dividend yields. Unfortunately, there is no such thing as a free lunch in the stock market. If a company is paying a dividend yield that is four or five times greater than the dividend yield of the S&P 500, there is a pretty strong chance that the dividend isn’t going to stick around. Companies that offer dividend yields of 7% or greater may seem alluring, but these high yields are often the result of a significant drop in a company’s share price and weak earnings that cannot support the company’s dividend over the long term.

A while back, a friend of mine invested in The Williams Companies (WMB) when it was trading at around $22.00. The company’s share price had taken a major hit and it was paying an annual dividend of $2.56, which works out to a yield of about 11.5%. As a novice dividend investor, he purchased the stock purely based on the company’s larger-than-average dividend. If he had done a little bit more research, he would have realized that the company only earned $0.84 per share in 2015 and there was no way that they could sustain their dividend. He received exactly two quarterly dividend payments at $0.64 each before the company announced it was cutting its annual dividend by 69% in the third quarter of 2016.

As an income investor, your goal is to get the best yield available on your money. This can make it very tempting to focus on dividend yield alone, but there are several other criteria that you should use to evaluate divided dividend stocks. You want to make sure that the company will be able to continue to pay out its current dividend by looking at important financial metrics including a company’s dividend payout ratio, debt, net margins, and return on equity. You will also want to determine if your dividend is likely to grow in the future, as evidenced by the company’s expected future earnings growth and its history of raising its dividend. You will also want to know whether or not you are paying a fair price for a dividend stock and are getting a historically competitive dividend yield. Use the criteria outlined in this chapter to evaluate each potential dividend stock purchase and you will have a pretty good idea whether or not the companies you are buying will be able to maintain and grow their dividend over time.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Dividend Yield

Dividend yield is simply the measure of what percentage of a company’s current share price is paid out in dividends each year. Let’s imagine that there is a company called PretendCorp that has a share price of $100.00 and it pays an annual dividend of $2.50. PretendCorp’s dividend yield is 2.5%. A company’s dividend yield will fluctuate throughout the day as the price of the company’s stock rises and falls with the market. If a company’s stock is doing exceptionally well, its dividend yield will fall as the stock’s share price rises. If PretendCorp’s share price were to rise to $150.00 and its dividend does not change at $2.50 per share, the company’s dividend yield would fall to 1.67%. If a company is getting hammered in the market and its price drops, the company’s dividend yield will rise. If PretendCorp were to post dismal earnings and its share price dropped to $50.00, its dividend yield would rise to 5.0%.

Focus on publicly traded companies that pay a dividend at least 50% higher than that of the S&P 500. As a stock investor who is looking for income, it only makes sense to focus on companies that pay a significantly higher yield than the broad-market indexes. As I write this guide, the S&P 500 offers a historically low dividend yield of 2.05%. That means the minimum dividend you should be looking for is 3.075% in today’s environment. On the other hand, you should treat companies that pay an unusually high dividend yield with a healthy level of skepticism. If a company’s dividend yield is more than three times greater than the dividend yield of the S&P 500, do extensive research about the company’s commitment to its dividend and its ability to maintain its dividend before investing your money. In today’s environment, that means you should evaluate a company that pays of 6.15% or higher with an extra amount of care and due diligence. Companies that pay extremely high dividend yields often come with outsized investment risks and their dividend may be at risk of being cut, but that doesn’t mean you should avoid dividend stocks with high yields entirely.

I personally focus my effort on companies that pay dividend yields between 3.5% and 6.5%. I consider this the “Goldilocks zone” or sweet spot of dividend yields. Companies that pay dividends in this range offer high-enough yields to pique our interest as dividend investors, but not so high that the dividend is unlikely to stay around in the future.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

History of Dividend Growth

If a company you are evaluating has an attractive dividend yield, the next step is to look at the history of dividend payments. How many years in a row has the company raised its dividend? Has the company ever cut its dividend during a recession? How much does the company raise its dividend every year, on average? Ultimately, we are looking for reliable dividend payments that are likely to steadily grow over time regardless of current market conditions. If a company has a track record of raising its dividend every year over the course of a couple of decades, there is a strong likelihood that it will continue along the same path of steadily raising its dividend if it is financially able to do so.

When I research a dividend stock, I pay special attention to what happened with the company’s dividend in 2008 and 2009 during the Great Recession. During the six-month period between September 2008 and October 2009, 46 companies on the S&P 500 reduced or eliminated their quarterly dividend payments. During the same period, 82 S&P 500 companies were able to raise their dividend through the depths of the Great Recession. Granted, some of those increases were token bumps so that companies could boast about their track record of raising their dividends every year. If a company was able to maintain and grow its dividend throughout 2008 and 2009 while the global economy was in bad shape, that’s a pretty good sign that the company is committed to its dividend and will be able to continue to making dividend payments during challenging economic times.

I personally focus on companies that have raised their dividend every year for at least the last 10 years. If a company has raised its dividend 10 years in a row, that is a pretty good indication that the company’s management is committed to growing its annual dividend. You should also read what the company’s management has to say about its dividend in its quarterly earnings reports and other public commentary to make sure that the company will continue to be committed to its dividend in the future. I also focus on companies that have grown their dividend by an average of 5% to 10% over the last three years. I am willing to accept lower dividend growth rates on companies that have dividend yields on the higher end of the 3.5% to 6.5% spectrum I target. For companies that have a dividend yield of less than 4%, I will want to see an annual dividend growth rate very close to 10%.

How fast your portfolio companies raise their dividend income will have a huge impact on the dividend income created by your portfolio over time. Let’s imagine that you owned a portfolio of dividend stocks that raise their dividend by an average of 7% each year. If you had a dividend portfolio that started out with a yield of 4.5%, you would be receiving dividend payments equal to 10.1% of your original investment after holding them for 12 years. After holding your investments for 25 years, you would be receiving dividend payments equal to 24.4% of your original investment each year.

[TIP: You can use MarketBeat.com to look up a company’s annual dividend, its dividend yield, its dividend payout ratio, its forward-looking dividend payout ratio, its track record of consecutive years of dividend growth, its 3-year average of annual dividend growth, and other important financial metrics. Simply head on over to MarketBeat.com in your favorite web browser and enter the ticker symbol of the stock you are researching in the search box. When that stock’s company profile page loads, click the “Dividends” tab to access these metrics.]

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Earnings Growth and Dividend Payout Ratio

A company’s track record of steadily raising their dividend and its management’s commitment to its dividend are always a good sign, but a company may be forced to reduce or eliminate its dividend if the company’s earnings can no longer support its dividend. Dividends are paid to shareholders out of earnings. If a company’s earnings are stagnant on a year-over-year basis, the company may not raise its dividend at all or it may merely issue a token dividend increase to maintain its track record of consecutively raising dividends every year. If a company’s earnings decline for several quarters in a row and it must pay out an unsustainably high percentage of its earnings as dividends, its board of directors may be forced to reduce or eliminate its dividend.

The measure which shows what percentage of a company’s earnings is being paid out as a dividend is known the dividend payout ratio. Dividend payout ratio is calculated by taking the company’s annual dividend and dividing it by its earnings per share. For example, Wells Fargo currently pays out an annual dividend of $1.52 per share. The company has posted earnings per share of $4.08 per share over the last four quarters. This would put Wells Fargo’s current dividend payout ratio at a healthy 37.2%.

You should also calculate a company’s forward-looking dividend payout ratio by dividing an average of analysts’ EPS estimates for the next fiscal year by its dividend. While a company may have a healthy dividend payout ratio now, you may be able to spot clouds on the horizon ahead if multiple analysts are forecasting a significant earnings decline in the coming quarters. If analysts were predicting that Wells Fargo’s earnings were going to drop by 50% over the next year to $2.04 per share (they’re not), its dividend payout ratio would rise to a much less healthy 74.5% and the continuation of its current dividend would be less of a sure thing.

The companies that you invest in as a dividend investor will generally have a relatively high dividend payout ratio. It only makes sense that companies that pay out strong dividends will pay out a significant portion of their earnings as dividends. Most of the companies that I personally invest in have dividend payout ratios between 40% and 70%. You should generally avoid companies that have a payout ratio higher than 75%, because there isn’t a lot of money left over to reinvest in the growth of the business and a short-term earnings hiccup could force the company to cut its dividend. However, a very high payout ratio does not mean a company will automatically cut its dividend. Companies tend to be reluctant to cut their dividends and will sometimes borrow money or use retained earnings to pay their annual dividend during periods of weak earnings.

Real estate investment trusts (REITs), business development companies (BDCs), and master limited partnerships (MLPs) are the two exceptions to the suggested 75% dividend payout ratio limit. REITs and BDCs are required by law to pay out 90% of their income to shareholders in the form of dividend. Logically, REITs and BDCs will generally have dividend payout ratios that exceed 90% because of this rule. While MLPs do not have the same requirement to pay out 90% of their income as distributions, they tend to have strong cash flow but weak reported earnings due to the capital-intensive nature of their businesses. Consequently, MLPs generally have very high reported dividend payout ratios.

When evaluating the sustainability of dividend payments for REITs and MLPs, calculate a company’s payout ratio based on its distributable cash flow rather than its reported earnings. Distributable cash flow is a measure of profitability that identifies how much money the company actually has to use for paying out dividends, reducing debt, investing in growth, or buying back its own shares. Distributable cash flow can be calculated by taking cash flow from operations minus capital expenditures, preferred dividends, debt service, and other one-time items. By dividing a REIT or MLP’s dividend per share into its distributed cash flow per share, you can calculate a ratio that will provide a better idea of the sustainability of the company’s dividend.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Debt

Banks will rarely lend more money to people that are already deeply in debt, because they know that consumers that have a heavy debt burden are already paying out a large percentage of their income in debt payments and simply don’t have the cash flow to make payments on new debt. Likewise, publicly traded companies that have a large amount of debt are often limited in their ability to return capital to shareholders in the form of dividends because much of their cash flow goes toward making debt payments. You can determine a publicly traded company’s debt burden by looking at its debt-to-equity ratio, which is simply the amount of debt the company has divided by the amount of shareholder equity. A debt-to-equity ratio of 1:1 is generally acceptable and any ratio lower than that is even better.

Debt-to-equity ratios will vary from industry to industry. In industries like telecommunications, manufacturing, and utilities, debt-to-equity ratios will be higher because companies in these industries use debt to finance long-term, large-scale projects. Companies in industries that have lower infrastructure requirements, such as consumer discretionary and consumer staples companies, will generally have lower debt-to-equity ratios. When evaluating a company’s debt-to-equity ratio, make sure to compare it to the debt-to-equity ratios of other companies in the same industry so that you are making a true apples-to-apples comparison of how much debt a company has compared to its competitors.

Return to the Table of Contents ▲

Profitability

A good way to determine whether or not a company will continue to have free cash flow to pay its dividend is by looking at the company’s net profit margins, which often gets shortened to “net margins.” Net margin is a metric that calculates the percentage of a company’s net revenue that is kept as profit. If a company has gross revenue of $1 billion and keeps $200 million as profit at the end of the year, it has a 20% net margin.